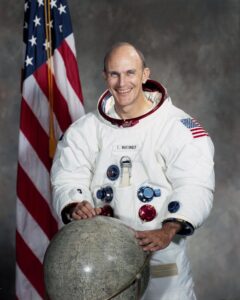

Ken Mattingly Will Have No More Birthdays

Long-time perusers of this web site may remember the birthday greetings issued here to Ken Mattingly following his 75th, 80th, and 85th birthdays. This morning at breakfast looking through the pages of the newspaper I noticed the photo above and knew why it would be appearing. Twelve years ago I started marking Admiral Mattingly’s milestone birthdays as a sign of how long it had been since men had ventured beyond low-earth orbit. Mattingly was the youngest of the twenty-four who had performed and experienced that feat, and the advanced age that he bore witnessed how long ago that was. Twelve years ago it seemed likely that Mattingly and his cohorts would all die before such a thing would be accomplished again by anyone, if ever. Such capability would pass into legend. NASA has a plan for the Artemis 2 mission to leave earth with four crew perhaps next November, though the wise bet would be to expect further delays. Frank Borman, commander of the first mission to venture thousands upon thousands of miles from the earth, also died this month. The deaths of Mattingly and Borman leave behind eight living lunar astronauts ranging in age from 95 to 88. If Artemis manages to send people to the moon in 2025 (which remains to be seen), it would be reasonable to expect a few more remaining Apollo astronauts to have died and for some to yet be alive.

While I have been using Ken Mattingly for my purposes, the world at large has had a different role for him: supporting character in one of their favorite movies. People really like Ron Howard’s 1995 Apollo 13. It seems like Apollo 13, thanks to that movie, figures bigger in people’s minds now than Apollo 11. The first 40% and last 10% of Mattingly’s Washington Post obituary are about the thing he didn’t do, launch as command module pilot of Apollo 13. He was famously grounded due to exposure to measles in the days before launch. The mission he did fly to the moon, Apollo 16, gets much less attention. I have a fascination with Apollo command module pilots, the most isolated men ever, a quarter of a million miles from the billions of people on earth, and up to a couple thousand miles from their two crewmates on the moon’s surface as they orbited alone for three days like Major Tom. That may never be duplicated. Back up is a good thing, but it is still questionable whether Artemis will eventually be able to perform the tasks Apollo did fifty years ago, and one piece of that is that Apollo could trust critical matters in the hands of a single competent man. Also, the return trajectory included a spacewalk by the command module pilot far from either the earth or the moon. They were the real spacemen of real spacemen.

As I wrote above Apollo 13 is currently the most popular lunar mission, and Apollo 11 is engraved is the history of mankind. My personal favorites are the first and the last, Apollo 8 and Apollo 17. Landing on the moon with boots and gloved hands was important, but just getting far, far, far away from earth means a lot for me, and Borman, Lovell, and Anders were the first to ever do that. Maybe it is the Nevadan in me who still loves the mood of a long drive and thinks a three-day drive to the moon and then three days back sounds great. A few summers ago a son and I read Frank Borman’s biography Countdown and I really liked the time spent with that. He was an uncomplicated, unsentimental, mission-oriented pilot. After the Apollo 11 landing he viewed the mission as accomplished, the mission of making sure communists and the rest of the world knew American expertise was quite sufficient to land a man, or a nuclear warhead, anywhere the nation felt it ought to put one. I cannot argue with Colonel Borman, but my perspective is different as one who was two years old when Borman flew to the moon and six when the last manned mission to the moon returned. I view the J missions, Apollo 15, 16, and 17 as the culmination of what Borman’s and Armstrong’s crews led the way to. Walking around for a couple hours was an important proof of concept and all that should have been done during what was still a testing phase. What was being tested (besides the reliability of American rockets to deliver payloads) was the ability to do what the J missions did: Work on the moon three days riding a dune buggy past the horizon and back.

Despite my attention to Ken Mattingly’s birthdays these past dozen years, of which there will be no more, I never read the transcript of his mission to the moon as I had some of the others. I hope I may do so in the days ahead. Here is one part of the voyage that was included in his obituary:

On the way back to Earth, Mr. Mattingly conducted a spaewalk to collect canisters of film and other materials.

He also found his wedding ring, which had vanished earlier in the mission. “Normally I found I could find things after a long period of time—they’d collect on the air filters,” he recalled. “But it never showed up.”

With the hatch open, Duke said, “Look at that.”

“And there was my wedding ring floating out the door,” Mr. Mattingly recalled. “I grabbed it, and we put it in the pocket. We had the chances of a gazillion to one.”

G.

November 21, 2023

One measure of decline is that for some people this is no longer a measure of decline.